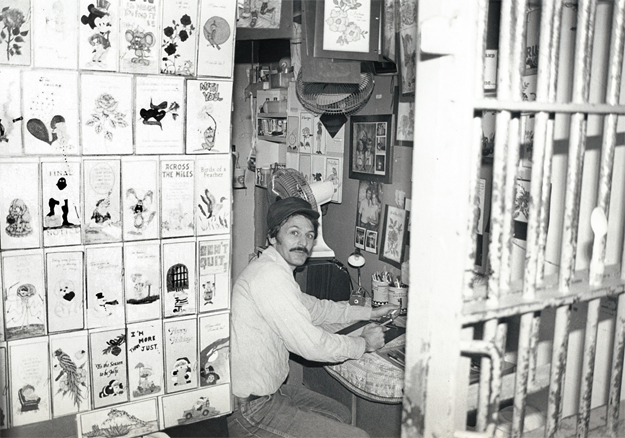

Tom Henry Living as a Free Man

Tom Henry, the title character of the book, Tom Henry: Confession of a Killer, was paroled last April. For 8 months he stayed with his sister and her husband in Central Illinois, near where he was born and raised, and where he committed his crime 50 years ago.

It was a community that protested his presence, and he worked diligently to transfer to another community in another state where he was known, not as a murderer, but as a hard-working logger, a husband, a father, a Bible-believing Christian, and a philanthropist. There he would be welcomed.

He got his wish in December and has since been living with his son, Thomas, in a mobile home they are refurbishing on a wooded acreage in southwestern Missouri, right in the hills where he hunted, fished, trapped, and logged during his 13 years as a fugitive.

I finally got the pleasure of visiting Tom Henry in his new milieu last weekend. At 72, he’s starting life afresh. He has re-established relationships with former friends and even with a new “friend,” his parole officer. (Below is a photo of him with Lou Keeling, former McDonald County sheriff, the very lawman who escorted the FBI to where Tom Elliott, nee Henry Hillenbrand, was logging some 35 years ago when he was returned into custody. Lou had said, You’re welcome back in this country when your legal problems get sorted out. )

He was born Henry Hillenbrand and he became Tom Elliott as a fugitive, thus the book title, Tom Henry. Now he is Tom Elliott to friends and neighbors and Henry Hillenbrand to his parole officer and Social Security. So, as senility approaches, his task is to keep his two identities straight.

Fortunately, he’s nowhere near senility yet and, hopefully, he won’t be for many years to come. His son supplied him with a pickup – 20 years old, stick shift, 6 cylinder, single cab – “couldn’t be more perfect,” he says. He hasn’t yet got his driver’s license; that’s next. He’s got feeders to attract deer and birds. He carries out seeds and molasses daily, and he looks out his living room window and watches them.

He’s free, except for a restriction not to leave the state, which is mildly onerous because he lives near where four states meet, but he doesn’t mind. “Actually, Bro, I don’t really want to leave this house much,” he tells me. “I really like it here.”

He happily cooks me breakfast, slicing and dicing bacon, veggies, potatoes, pacing and talking a mile a minute. A friend gave him a drip coffee pot, which he keeps going all day. He takes long walks in the woods nearby and down by the creek that flows in the ravine. The local Goodwill Store has become his haberdashery.

He is content and relaxed. I sit in an easy chair watching him watch the birds through his picture window and we’re both happy.